“Toxicity is in the dose.”

Envenomation is a process by which a venom or toxin is injected into another being via a bite, puncture or sting. Envenomation is always due to direct contact with an animal (or parts of it like drifting jellyfish tentacles). There are two possible mechanisms of injection: active, such as jellyfish or cone snails, or passive like lionfish or sea urchins. Injuries typically occur during shore entries or exits, incidental contact or deliberate attempts to handle a specimen. Envenomations are rare but can be life-threatening and may require rapid first aid response. In this chapter, we will cover some common envenomations as well as some of the more rare, but serious cases.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

Fire Coral

Fire corals are colonial marine cnidarians that when touched can cause burning skin reactions. Fire coral-related incidents are common among divers with poor buoyancy control.

Biology and Identification

Fire coral, which belong to the genus Millepora, are found in tropical and subtropical waters around the world. Generally fire coral adopts a yellow-green or brownish branchy formation, although its external appearance often varies due to environmental factors. Because fire coral can colonize hard structures, it can even adopt a rather stony appearance with rusty coloration.

Despite their calcareous structure, fire coral is not a true coral; these animals are more closely related to Portuguese man-of-war and other hydrozoans.

Mechanism of Injury

Fire coral gets its name because of the fiery sensation experienced after coming into contact with a member of the species. The mild to moderate burning that it causes is the result of cnydocites embedded in its calcareous skeleton; these cnydocites contain nematocysts that will fire when touched, injecting their venom.

Signs and Symptoms

The burning sensation may last several hours and is often associated with a skin rash that appears minutes to hours after contact. This skin rash can take several days to resolve. Often, the skin reaction will subside in a day or two, but it may likely reappear several days or weeks after the initial rash disappeared.

Fire coral lacerations, in which an open wound receives internal envenomation, are the most problematic fire coral injuries. Venom from Millepora spp. is known to cause tissue necrosis on the edges of a wound. These injuries should be carefully observed, as necrotic tissue provides a perfect environment to culture serious soft tissue infections.

Prevention

- Avoid touching these calcareous formations.

- If you need to kneel on the bottom, look for clear sandy areas.

- Remember that hard surfaces such as rocks and old conchs may be colonized by fire coral even if they do not look branchy.

- Always wear full-body wetsuits to provide protection against the effects of contact.

- Master buoyancy control.

- Always look down while descending.

First Aid

- Rinse the affected area with household vinegar.

- Redness and vesicles will likely develop. Do not puncture them; just let them dry out naturally.

- Keep the area clean, dry and aerated—time will do the rest.

- For open wounds, seek a medical evaluation.

NOTE: Fire coral venom is known to have dermonecrotic effects. Share this information with your physician before any attempts to suture the wound, as the wound edges might become necrotic. - Antibiotics and a tetanus booster may be necessary

Portuguese Man-of-War

Portuguese man-of-wars are free-floating cnidarians characterized by blue gas-filled bladders and long tentacles that drift on the surface of the ocean. Contact with a man-of-war’s tentacles can cause intense pain and other systemic symptoms.

Biology and Identification

There are two species for the genus: Physalia physalis in the Atlantic and Physalia utriculus in the Indo-Pacific. The Atlantic man-of-war may reach slightly larger dimensions, with the gas bladder rarely exceeding one foot (30 centimeters) and tentacles averaging 33 feet (10 meters) and possibly extending up to 165 feet (50 meters).

Though many people mistake the Portuguese man-of-war for species of jellyfish, this genus belongs to the order Siphonophora, a class of hydrozoans. What we see as a single specimen is actually a colony composed of up to four different types of polyps. Despite its resemblance, these animals are more closely related to fire coral than to jellyfish.

The Portuguese man-of-war is easily recognizable; if you see blue tentacles, you can bet they belong to Physalia.

Risk to Humans

The man-of-war’s polyps contain cnidocytes delivering a potent proteic neurotoxin capable of paralyzing small fish. For humans, most stings cause red welts accompanied by swelling and moderate to severe pain. These local symptoms last for two to three days.

Systemic symptoms are less frequent, but potentially severe. They may include generalized malaise, vomiting, fever, elevated heart rate at rest (tachycardia), shortness of breath and muscular cramps in the abdomen and back. Severe allergic reactions to the man-of-war’s venom may interfere with cardiac and respiratory function, so divers should always seek a timely professional medical evaluation.

Epidemiology

Approximately 10,000 cnidaria envenomations occur each summer off the coasts of Australia, the vast majority

of which involve Physalia. In fact, man-of-wars cause the most cnidarian envenomations prompting emergency evaluation globally. The risk may not be so great for divers, however, as most Physalia stings occur on beaches or on the surface of the water rather than while submerged. Certain regions are known to have seasonal outbreaks, but incidence is highly variable between regions.

Prevention

- Always look up and around while surfacing. Pay special attention during the last 15-20 feet of your ascent, since this is the area where you may find cnidarians and their submerged tentacles.

- Wear full body wetsuits regardless of water temperature. Mechanical protection is the best way to prevent stings and rashes.

- In areas where these animals are known to be endemic, a hooded vest may be the best way to protect your neck.

First Aid

- Avoid rubbing the area. Cnidarian tentacles are like nematocyst-coated spaghetti, so rubbing the area or allowing the tentacles to roll over the skin will exponentially increase the affected surface area and, therefore, the envenomation process.

NOTE: Initial pain may be intense. Though life-threatening complications are rare, monitor circulation, airway and breathing, and be prepared to perform CPR if necessary. - Remove the tentacles. You must take great care to remove the man-of-war’s tentacles in order to avoid further envenomation. Those distinctive blue tentacles are quite resistant to traction, so you can remove them fairly easily with some tweezers or gloves.

NOTE: If you do not have access to tweezers or gloves, the skin on your fingers is likely thick enough to protect you. Keep in mind, however, that after removal your fingers may contain hundreds or even thousands of unfired nematocysts, so pretend you have been handling hot chili peppers that cause blisters anywhere you touch and treat your fingers as recommended from the next step on. - Flush the area with seawater. Once the tentacles and any remnants have been removed, use a high volume syringe and flush the area with a powerful stream of seawater to remove any remaining unfired nematocysts. Never use freshwater since this will cause unfired nematocysts to fire.

- Apply heat. Immerse the affected area in hot water (upper limit of 113°F/45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes. If you are assisting a sting victim, try the water on yourself first to assess tolerable heat levels. Do not rely on the victim’s assessment, as intense pain may impair his ability to evaluate tolerable heat levels. If you cannot measure water temperature, a good rule of thumb is to use the hottest water you can tolerate without scalding. Note that different body areas have different tolerance to heat, so test the water on the same area where the diver was injured. Repeat if necessary. If hot water is not available, apply a cold pack or ice in a dry plastic bag.

NOTE: Application of heat has two purposes: 1) it may mask the perception of pain; and 2) it may assist in thermolysis. Since we know the venom is a protein that has been superficially inoculated, application of heat may help by denaturing the toxin. - Always seek an emergency medical evaluation.

- Continue monitoring the patient until a higher level of care has been reached.

Vinegar Application

Use of vinegar is controversial with Physalia spp. Though the use of vinegar has traditionally been recommended, several studies both in-vivo and in-vitro show massive nematocyst discharge upon pouring household vinegar over certain species of cnidarians, including Physalia. Still, the most current American Heart Association guidelines (AHA 2010) recommend application of vinegar for all jellyfish, including Physalia spp. If anything changes, DAN will let you know.

If you do choose to apply vinegar, you can optimize application and significantly economize by using spray bottles. Generously spray the area with vinegar for no less than 30 seconds to neutralize any invisible remnants. Pick off any remaining tentacles.

Lionfish

The lionfish is a genus of venomous fish commonly found in tropical reefs. Native to the Indo-Pacific, the fish is one of the most infamous invasive species in the western Atlantic. This voracious predator is not a threat to divers, but its introduction into exotic ecosystems can decimate juvenile specimens. In an attempt to control the spread of lionfish populations, recreational divers in the Americas have started aggressive campaigns to hunt them; in the process, many divers are stung with the lionfish’s sharp spines, which can cause very painful and sometimes complicated wounds.

Identification and Distribution

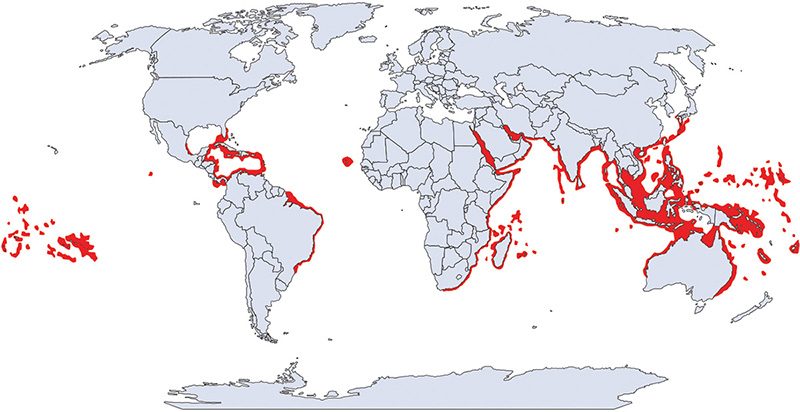

Lionfish, turkeyfish and zebrafish are common names for fish species of the genus Pterois, a subset of fish of the venomous Scorpaenidae family. Though lionfish are native to the Indo-Pacific, members of the family Scorpaenidae can be found in oceans all over the globe, even in arctic waters. Lionfish specimens are typically red with white and black stripes and have showy, spiky fins. Species include Pterois volitans, P. miles, P. radiata, and P. antenata among a few others.

Western Atlantic Invasion

Since the early 1990s, invasive lionfish have wreaked havoc on local juvenile reef fish populations in the western Atlantic. Out of the nine species of Pterois, only P. volitans and P. miles are found in Western Atlantic waters, but they range from as far north as Rhode Island down to Venezuela and The Guianas.

Risk to Humans

Knowing no predators, these fish are generally docile, allowing divers to approach closely enough and making themselves easy targets for spearfishing. Unfortunately, the desperate attempts to eradicate these fish from the Americas have caused a significant rise in the incidence of lionfish puncture wounds.

Epidemiology

The prevalence and incidence of lionfish envenomations is unknown. Treating physicians may not choose to consult a poison control center, and in the United States are under no obligation to report these injuries to state or federal agencies. Scientific literature accounts for 108 cases of lionfish envenomations reported between 1976 and 2001, and almost all of these reports are actually from marine aquarists. It is impossible to know how often victims go untreated and how often treatment goes unreported, but the frequency of case reports seems to indicate that lionfish envenomations are not uncommon.

Lionfish culling tournaments are becoming more and more popular all over the Caribbean. Recent studies conducted by DAN staff from Cozumel, Mexico accounted over four years of tournaments. Incidence of injury during these events was between 7-10% of participants.

Mechanism of Injury

Most lionfish-related incidents occur as a result of careless handling, usually during spearfishing or while preparing them for consumption. Lionfish have needlelike spines located along the dorsal, pelvic and anal fins, and punctures can be extremely painful and lead to rapid development of localized edema and subcutaneous bleeding. Pain can last for several hours, edema typically resolves in two to three days, and tissue discoloration can last up to four or five days. Due to edema and the venom’s inherent toxicity, puncture wounds on fingers can lead to ischemia (restriction of blood supply to the tissues) and necrosis.

Prevention

Lionfish are by no means aggressive. To prevent injuries, maintain a prudent distance. If you are committed to engage in spearfishing or culling activities, avoid improvisations and do not try to handle these animals until you learn from more experienced divers.

First Aid

If you are stung, remain calm. Notify the dive leader and your buddy. The priority is to safely end your dive, returning to the surface following a normal ascent rate. Do not skip any decompression obligation.

On the surface, first aid providers should:

- Rinse the wound with clean freshwater.

- Remove any obvious foreign material.

- Control bleeding if needed. It is ok to allow small punctures to bleed for a minute immediately after being stung (this may decrease venom load).

- Apply heat. Immerse the affected area in hot water (upper limit of 113°F/45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes. If you are assisting a sting victim, try the water on yourself first to assess tolerable heat levels. Do not rely on the victim’s assessment, as intense pain may impair his ability to evaluate tolerable heat levels. If you cannot measure water temperature, a good rule of thumb is to use the hottest water you can tolerate without scalding. Note that different body areas have different tolerance to heat, so test the water on the same area where the diver was injured. Repeat if necessary.

NOTE: Thermolysis can also be a secondary benefit worth pursuing, but it tends to be less effective in cases where the venom has been injected deep into the tissues. - Apply bandaging as needed.

- Seek a professional medical evaluation.

Blue-Ringed Octopus

Blue-ringed octopus are a small species of venomous octopi that live in tropical tide pools from south Japan to the coastal reefs of Australia and the western Indo-Pacific. These small octopi are the only cephalopods known to be dangerous to humans.

Identification

The blue-ringed octopus hardly ever exceeds eight inches (20 centimeters) in size. Their most distinctive feature is the blue iridescent rings that cover their yellow-colored body; however, it is important to emphasize that this feature is only displayed when the animal is disturbed, hunting or mating. When calm or at rest, the animal may display an overall yellowish, grey or beige coloration without any visible blue rings. The blue-ringed octopus is more active at night, spending most of the day hidden in its nest in shallow areas or tide pools.

Epidemiology

Blue-ringed octopus envenomations are very rare. These animals are only endemic to southern Japan, Australia and the western Indo-Pacific. Cases outside of this region are generally due to deliberate handling of aquarium specimens. There are only a handful of reported fatal cases. Full recovery is expected with timely professional medical intervention.

Mechanism of Injury

As with all cephalopods, octopi have a strong beak similar to those of parrots and parakeets. All octopi have some sort of venom to paralyze their victims, but the blue-ringed octopus bite may contain an extremely powerful neurotoxin called tetrodotoxin (TTX), which can be up to 10,000 times more potent than cyanide and can paralyze a victim in minutes. Theoretically, a little over one-half milligram of this venom—the amount that can be placed on the head of a pin—is enough to kill an adult human. Certain bacteria present in the blue-ringed octopus’ salivary glands synthesize the toxin. TTX is not unique to the blue-ringed octopus; certain newts, dart frogs, cone snails and pufferfish can also be a source of TTX intoxication, though from different mechanisms.

Signs and Symptoms

A blue-ringed octopus bite is usually painless or no more painful than a bee sting; however, even painless bites should be taken seriously. Neurological symptoms dominate every stage of envenomation, and manifest as paresthesia (tingling and numbness) progressing to paralysis that could potentially culminate in death. If envenomation has occurred, signs and symptoms usually start within minutes and may include paresthesia of the lips and tongue. This is usually followed by excessive salivation, trouble with pronunciation (dysarthria), difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), sweating, dizziness and headache. Serious cases may progress to muscular weakness, incoordination, tremors and paralysis. Paralysis may eventually affect respiratory muscles, which can lead to severe hypoxia with cyanosis (blue or purple tissue discoloration due to insufficient oxygen in the blood).

Prevention

These animals are not aggressive, and divers should not fear blue-ringed octopi. If encountered, avoid handling these animals. Due to their small size and lack of skeleton, a blue-ringed octopus den might be a small space only accessible through a tiny crevice, so avoid picking up bottles, cans or mollusk shells in areas they inhabit.

First Aid

Care is supportive. There is no antivenom available. If someone is bitten:

- Clean the wound with freshwater and provide care for a small puncture wound.

- Apply the pressure immobilization technique.

NOTE: TTX is a heat-stable toxin, so the application of heat will not denature the toxin. - Watch for signs and symptoms of progressive paralysis.

- Be prepared to provide mechanical ventilations with a bag valve mask device or a manually triggered ventilator.

- Do not wait for signs and symptoms of paralysis. Always seek an evaluation at the nearest emergency department.

NOTE: The bite site might be painless and still be lethally toxic.

- Wound excision is never recommended.

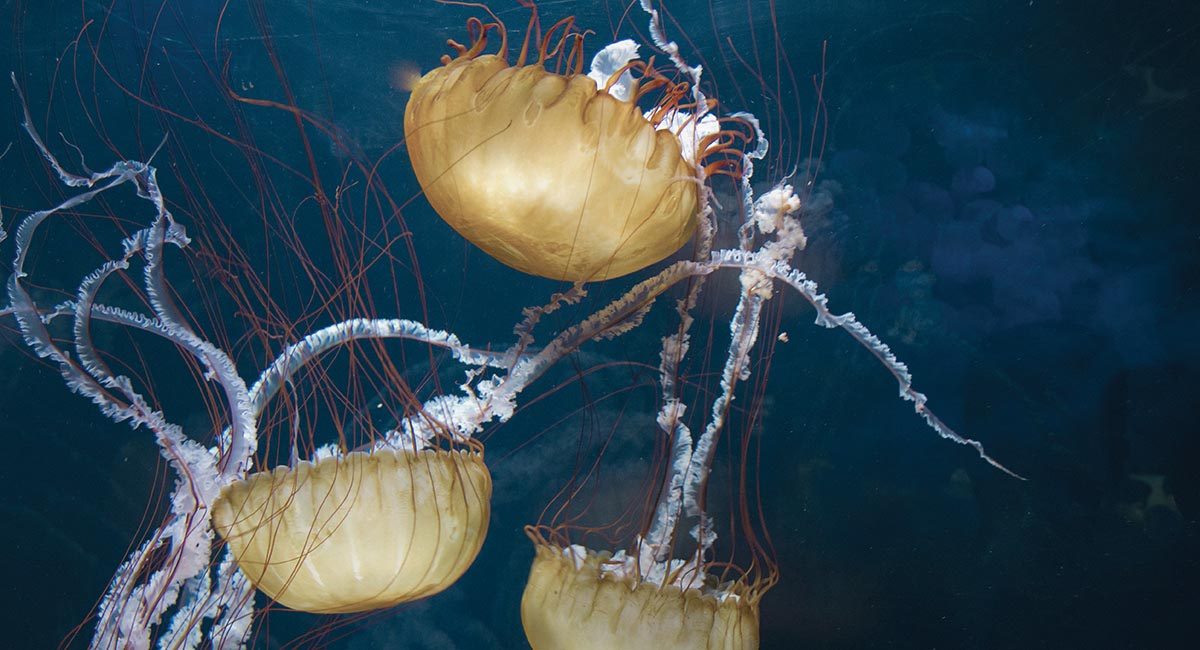

Box Jellyfish

Box jellyfish (cubozoans) are cube-shaped medusa notorious for possessing one of the most potent venoms known to mankind. Certain species can kill an adult human in as little as three minutes, scarcely enough time for any rescue response.

Biology and Identification

Medusas are the migrant form of cnidarians. In the case of box jellyfish, their bell-like body is cube shaped, with tentacles extending from each corner. Box jellyfish are complex animals with a propulsion mechanism and a relatively sophisticated nervous system for a jellyfish. They have up to 24 eyes, some of them with corneas and retinas, enabling them to not only detect light but also to see and circumnavigate objects to avoid collision.

While some jellyfish live off of symbiotic algae, box jellyfish prey on small fish, which are immediately paralyzed upon contact with their tentacles. Then the tentacles are retracted, carrying the prey into the bell for digestion. Some species hunt daily, and at night some species can be observed resting on the ocean floor.

Epidemiology and Distribution

From 1884 to 1996, there were more than 60 reported fatalities from box jellyfish stings in Australia. There are species of box jellyfish in almost all tropical and subtropical seas, but life-threatening species seem to be restricted to the Indo-Pacific.

Notorious Species

SEA WASP

Found in the coastal waters of Australia and Southeast Asia, sea wasp is the common name for the most dangerous cnidarian: Chironex fleckerii. The largest cubozoan, sea wasps have a bell approximately eight inches (20 centimeters) in diameter and tentacles ranging from a few centimeters to up to 10 feet (three meters). Contact with these animals triggers the most powerful and lethal envenomation process known to science. Sea wasp envenomation causes immediate excruciating pain followed by cardiac failure. Death may occur in as little as three minutes.

Recent studies have identified a component of the venom that drills a hole in red blood cells, causing a massive release of potassium, possibly responsible for the lethal cardiovascular depression. The same study may have also identified a way to inhibit this effect, which in the coming years could prove to be clinically promising.

FOUR-HANDED BOX JELLYFISH

The four-handed box jellyfish (Chiropsalmus quadrumanus) habitat spans from South Carolina to the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and as far south as Brazil. The four-handed box jellyfish can inflict extremely painful stings and is the slightly smaller American cousin to the Australian sea wasp. There is one documented case of a four-year-old boy who was stung in the Gulf of Mexico and died within 40 minutes.

BONAIRE BANDED BOX JELLYFISH

Bonaire banded box jellyfish (Tamoya ohboya) is a relatively unknown, highly venomous species found in the Dutch Caribbean. Since 1989, there have been roughly 50 confirmed sightings primarily in Bonaire with the remainder on the shores of Mexico, St. Lucia, Honduras, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. There have only been three reported cases of envenomation, which lead to intense pain and skin damage; only one case required hospitalization.

IRUKANDJI SYNDROME

Tiny box jellyfish found near Australia, Carukia barnesi and Malo kingi, are responsible for the infamous and extremely painful symptomatic complex known as Irukandji syndrome. These small cubozoans’ bells are only a few millimeters with tentacles up three feet (one meter). Fortunately, fatalities from these smaller species are rare, but stings are extremely painful and can cause systemic symptoms including cardiovascular instability that should prompt immediate medical attention. Survivors have reported a feeling of impending doom, claiming they were certain that they could not survive such intense, generalized pain; however, it is important to emphasize that a single sting should not be fatal.

Though stings from lesser-known species of cubozoans are not necessarily lethal, they can still be very painful. An immediate medical evaluation is always recommended.

Prevention

- Properly research the areas you intend to dive.

- Avoid known box jellyfish habitats if you are not sure the dive site or swimming area is safe. If stung, cardiovascular stability can rapidly deteriorate with very little time for any effective field intervention.

- In Northern Queensland, Australia, net enclosures are placed in the water where box jellyfish are known to be during summer months (November to May), but these cannot guarantee safety.

- Minimize unprotected areas. Always wear full wetsuits, hoods, boots and gloves. Something as simple as nylon pantyhose worn over the skin will prevent jellyfish stings.

- Carry sufficient household vinegar with you to all dive sites.

First Aid

If stung by any jellyfish, follow these procedures in this order:

- Activate local emergency medical services.

- Monitor victim’s airway, breathing and circulation. Be prepared to perform CPR at any moment (particularly if you suspect box jellyfish).

- Avoid rubbing the area. Box jellyfish tentacles can be cylindrical or flattened, but they are coated with cnydocites, so rubbing the area or allowing the tentacles to roll over the skin will exponentially increase the affected surface area and the envenomation process.

- Apply household vinegar to the area. Generously pour or spray the area with vinegar for no less than 30 seconds to neutralize any invisible remnants. You can pour the vinegar over the area or use a spray bottle, which optimizes application. Let the vinegar stand for a few minutes before doing anything else.

NOTE: This will not do anything to the pain or the venom already injected, but it is intended to stabilize any remaining unfired nematocysts on the diver’s skin before you try to remove them. - Wash the area with seawater (or saline). Use a syringe with a steady stream of water to help remove any tentacle remains. Do not rub.

NOTE: Do not use freshwater; this could cause massive nematocyst discharge. - Apply heat. Immerse the affected area in hot water (upper limit of 113°F/45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes. If you are assisting a sting victim, try the water on yourself first to assess tolerable heat levels. Do not rely on the victim’s assessment, as intense pain may impair his ability to evaluate tolerable heat levels. If you cannot measure water temperature, a good rule of thumb is to use the hottest water you can tolerate without scalding. Note that different body areas have different tolerance to heat, so test the water on the same area where the diver was injured. Repeat if necessary. If hot water is not available, apply a cold pack or ice in a dry plastic bag.

NOTE: Application of heat has two purposes: 1) it may mask the perception of pain; and 2) it may assist in thermolysis. Since we know the venom is a protein that has been superficially inoculated, application of heat may help by denaturing the toxin. - Always seek an emergency medical evaluation.

Cone Snails

Cone snails are marine gastropods characterized by a conical shell and beautiful color patterns. Cone snails possess a harpoon-like tooth capable of injecting a potent neurotoxin that can be dangerous to humans.

Identification and Distribution

There are about 600 different species of cone snails, all of which are poisonous. Cone snails live in shallow reefs partially buried under sandy sediments, rocks or corals in tropical and subtropical waters. Some species have adapted to colder waters.

Mechanism of Injury

Injuries typically occur when the animal is handled. Cone snails administer stings by extending a long flexible tube called a proboscis and then firing a venomous, harpoonlike tooth (radula).

Signs and Symptoms

A cone snail sting can cause mild to moderate pain, and the area may develop other signs of acute inflammatory reaction like redness and swelling. Conustoxins affect the nervous system and are capable of causing paralysis possibly leading to respiratory failure and death.

Epidemiology

The prevalence and incidence of cone snails envenomations is unknown, but it is probably a very rare occurrence in divers and the general population. Shell collectors (professional or amateur) may be at higher risk.

Prevention

If you see a beautiful marine snail that looks like a cone, it is probably a cone snail. It is difficult to tell whether a cone snail inhabits a given shell as they are able to hide inside them. Since all cone snails are venomous, err on the side of safety and do not touch it.

First Aid

Unfortunately, there is no specific treatment for cone snail envenomations. First aid focuses on controlling pain, but may not influence outcomes. Envenomation will not necessarily be fatal, but depending on the species, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s size and susceptibility, complete paralysis may occur and this may lead to death. Cone snail venom is a mixture of many different substances including tetrodotoxin (TTX).

- Clean the wound with freshwater and provide care for a small puncture wound.

- Apply the pressure immobilization technique.

NOTE: Application of heat might help with pain management, but since TTX is a heat-stable toxin, the application of heat will not denature the toxin. - Watch for signs and symptoms of progressive paralysis.

- Be prepared to provide mechanical ventilations with a bag valve mask device or a manually triggered ventilator.

- Do not wait for signs and symptoms of paralysis. Always seek an evaluation at the nearest emergency department.

NOTE: The bite site might be painless and still be lethally toxic.